Great by choice is a book about research that answers the question: why do some companies thrive in uncertainty, even chaos, and others do not?

The book is based on research, has many examples and very engaging. It serves all of that with amazing structure including handy chapter summaries.

It is a bit too detailed to my liking in some places.

Below are my favourite highlights

Update: I read some criticism of Jim’s research and there are some very strong points. While his research methods might be good (there are enough criticism about it as well) the issue lies in a small pool of companies. Statistically it’s very easy to get false positive when you have only 20 companies to look at.

There are two videos which expand on the issue with such research - About p-hacking: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=42QuXLucH3Q - And how data is random https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1tSqSMOyNFE

1. Thriving in Uncertainty

We cannot predict the future. But we can create it.

2. 10Xers

Victory awaits him who has everything in order—luck people call it. Defeat is certain for him who has neglected to take the necessary precautions in time; this is called bad luck.

— Roald Amundsen The South Pole

10Xer (pronounced “ten-EX-ers”) is a winning protagonists named in the research, because they built enterprises that beat their industry’s averages by at least 10 times.

10Xers vs successful comparisons:

- They’re not more creative.

- They’re not more visionary.

- They’re not more charismatic.

- They’re not more ambitious.

- They’re not more blessed by luck.

- They’re not more risk seeking.

- They’re not more heroic.

- They’re not more prone to making big, bold moves.

Amundsen’s philosophy: You don’t wait until you’re in an unexpected storm to discover that you need more strength and endurance. You don’t wait until you’re shipwrecked to determine if you can eat raw dolphin. You don’t wait until you’re on the Antarctic journey to become a superb skier and dog handler. You prepare with intensity, all the time, so that when conditions turn against you, you can draw from a deep reservoir of strength. And equally, you prepare so that when conditions turn in your favor, you can strike hard.

10Xers understand that they face continuous uncertainty and that they cannot control, and cannot accurately predict, significant aspects of the world around them. On the other hand, 10Xers reject the idea that forces outside their control or chance events will determine their results; they accept full responsibility for their own fate.

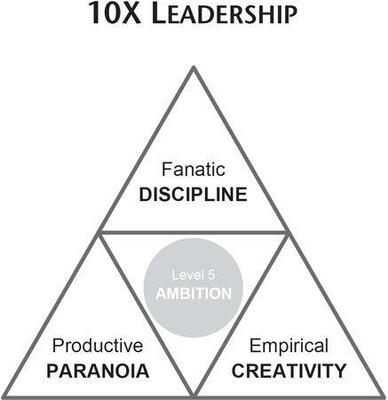

10X leadership

Fanatic Discipline

their behavior fits nowhere on a normal curve.

10Xers display extreme consistency of action—consistency with values, goals, performance standards, and methods. They are utterly relentless, monomaniacal, unbending in their focus on their quests.

Empirical Creativity

When faced with uncertainty, 10Xers do not look primarily to other people, conventional wisdom, authority figures, or peers for direction; they look primarily to empirical evidence. They rely upon direct observation, practical experimentation, and direct engagement with tangible evidence. They make their bold, creative moves from a sound empirical base.

The 10Xers had a much deeper empirical foundation for their decisions and actions, which gave them well-founded confidence and bounded their risk.

The 10Xers don’t favor analysis over action; they favor empiricism as the foundation for decisive action.

Productive Paranoia

Fear should guide you, but it should be latent,

I consider failure on a regular basis.— Bill Gates 1994

10Xers maintain hypervigilance, staying highly attuned to threats and changes in their environment, even when—especially when—all’s going well. They assume conditions will turn against them, at perhaps the worst possible moment. They channel their fear and worry into action, preparing, developing contingency plans, building buffers, and maintaining large margins of safety.

overconfidence leads to doom

Level 5 Ambition

10Xer we studied aimed for much more than just “becoming successful.” … They’re passionately driven for a cause beyond themselves.

3. 20 Mile March (Fanatic Discipline)

The 20 Mile March creates two types of self-imposed discomfort: (1) the discomfort of unwavering commitment to high performance in difficult conditions, and (2) the discomfort of holding back in good conditions.

The 20 Mile March imposes order amidst disorder, consistency amidst swirling inconsistency. But it works only if you actually achieve your march year after year.

A good 20 Mile March has the following seven characteristics:

-

Clear performance markers.

-

Self-imposed constraints.

-

Appropriate to the specific enterprise.

-

Largely within the company’s control to achieve.

-

A proper timeframe—long enough to manage, yet short enough to have teeth.

-

Imposed by the company upon itself.

-

Achieved with high consistency.

20 Mile Marching helps turn the odds in your favor for three reasons:

-

It builds confidence in your ability to perform well in adverse circumstances.

-

It reduces the likelihood of catastrophe when you’re hit by turbulent disruption.

-

It helps you exert self-control in an out-of-control environment.

Having a clear 20 Mile March focuses the mind; because everyone on the team knows the markers and their importance, they can stay on track.

4. Fire Bullets, Then Cannonballs (Empirical Creativity)

the 10X companies were less innovative than the comparisons.

It seems that pioneering innovation is good for society but statistically lethal for the individual pioneer!

Once a company meets the threshold of innovation necessary for survival and success in a given environment, it needs a mixture of other elements to become a 10X company—in particular, the mixture of creativity and discipline.

Intel’s founders believed that innovation without discipline leads to disaster.

The simplistic mantra “innovate or die” should be replaced with a much more useful idea: fire bullets, then fire cannonballs.

We call a cannonball fired before you gain empirical validation an uncalibrated cannonball. The 10Xers were much more likely to fire calibrated cannonballs, while the comparison cases had uncalibrated cannonballs flying all over the place.

For most of its history, Progressive Insurance lived by an explicit guideline to prevent uncalibrated cannonballs: limit any new business to 5 percent of total corporate revenues until fine-tuned for sustained profitability.

5. Leading above the Death Line (Productive Paranoia)

Productive Paranoia 1: Extra Oxygen Canisters-It’s What You Do Before The Storm Comes

Compared to the median cash-to-assets ratio for 87,117 companies analyzed in the Journal of Financial Economics, the 10X companies carried 3 to 10 times the ratio of cash to assets.

10Xers remain productively paranoid in good times, recognizing that it’s what they do before the storm comes that matters most. When a calamitous event clobbers an industry or the overall economy, companies fall into one of three categories: those that pull ahead, those that fall behind, and those that die.

Productive Paranoia 2: Bounding Risk

10X took less Death Line risk, less asymmetric risk, and less uncontrollable risk than the comparison cases.

go slow when you can, fast when you must.

Focus on superb execution once decisions are made; intensity increased as needed to meet time demands without compromising excellence.

We concluded that recognizing a change or threat early, and then taking the time available—whether that be short or long—to make a rigorous and deliberate decision yields better outcomes than just making a bunch of quick decisions.

How much time before our risk profile changes?

Productive Paranoia 3: Zoom Out, Then Zoom In

Zoom Out

-

Sense a change in conditions

-

Assess the time frame: How much time before the risk profile changes?

-

Assess with rigor: Do the new conditions call for disrupting plans? If so, how?

Zoom In

- Focus on supreme execution of plans and objectives

6. SMaC

SMaC stands for Specific, Methodical, and Consistent. The more uncertain, fast-changing, and unforgiving your environment, the more SMaC you need to be.

All the 10X companies’ SMaC recipes contained things not to do.

Never let a weak member attempt to summit. “A team is only as strong as its weakest member.”

But in fact, the existence of a recipe per se did not systematically distinguish the 10X companies from the comparison companies. Rather, the principal finding is how the 10X companies adhered to their recipes with fanatic discipline to a far greater degree than the comparisons, and how they carefully amended their recipes with empirical creativity and productive paranoia.

We’ve found in all our research studies that the signature of mediocrity is not an unwillingness to change; the signature of mediocrity is chronic inconsistency.

There are two healthy approaches to amending the SMaC recipe: (1) exercising empirical creativity, which is more internally driven, and (2) exercising productive paranoia, which is more externally focused. The first involves firing bullets to discover and test a new practice before making it part of the recipe. The second employs the discipline to zoom out to perceive and assess a change in conditions, then to zoom in to implement amendments as needed.

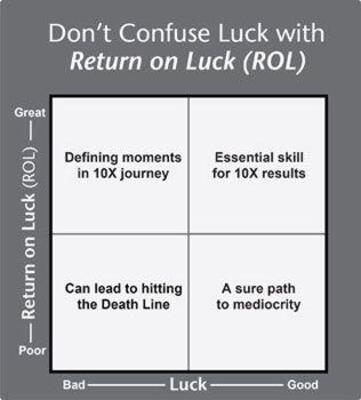

7. Return on Luck

None of these often repeated phrases are precise enough to actually analyze the role of luck, so we constructed a definition that would allow us to engage directly with the topic, focusing on identifying specific luck events.

-

Luck is where preparation meets opportunity

-

Luck is the residue of design

-

The harder I work, the luckier I get.

The critical question is not “Are you lucky?” but “Do you get a high return on luck?”

A single stroke of good luck, no matter how big the break, cannot by itself make a great company. But a single stroke of extremely bad luck that slams you on the Death Line, or an extended sequence of bad-luck events that creates a catastrophic outcome, can terminate the quest.

Luck favors the persistent, but you can persist only if you survive.

The essence of “managing luck” involves four things:

-

cultivating the ability to zoom out to recognize luck when it happens

-

developing the wisdom to see when, and when not, to let luck disrupt your plans

-

being sufficiently well-prepared to endure an inevitable spate of bad luck

-

creating a positive return on luck—both good luck and bad—when it comes.

Luck is not a strategy, but getting a positive return on luck is.

10Xers grasp that if they blame bad luck for failure, they capitulate to fate. Equally, they grasp that if they fail to perceive when good luck helped, they might overestimate their own skill and leave themselves exposed when good luck runs dry.

Other (FAQ)

John Brown at Stryker had a gift for picking the right people and the discipline to move people out of seats in which they were failing, following a Stryker philosophy that it’s better to invest heavily in the right people than to pour too much energy into people who aren’t going to make it.

All the 10X companies cultivated cult-like cultures wherein the right people would flourish and equally, where the wrong people would quickly self-eject.

The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.

— F. Scott Fitzgerald

The premise behind this work is that instability is chronic, uncertainty is permanent, change is accelerating, disruption is common, and we can neither predict nor govern events.